The Role of Boards in Measuring and Managing Culture

by BOB BARBOUR, SEAN BOWMAN & JOEL BENDALL, Stagira Consulting

This article was originally published in Governance Directions, November 2019, Governance Institute of Australia

Executive Summary

- Companies and boards that are not planning to assess and manage culture are, in the words of Commissioner Hayne, ‘foolish and ignorant’

- Many companies think they are measuring culture, but are instead measuring talent and/or engagement

- Culture should be viewed in the context of an overall organisational construct – with an end goal of sustainable marketplace success.

Culture and the Banking Royal Commission

The Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (“banking royal commission”) was a watershed moment for organisational culture.

Before the Hayne Royal Commission, culture was seen as largely a managerial responsibility, and not something that most Boards saw requiring independent inquiry or their oversight. Sure, the James Hardie case highlighted the importance of managing the culture of the Board itself. But the organisation’s culture strategy, if there was one, was largely left to management and HR.

The Hayne Royal Commission changed all of this, and probably forever. When culture emerged as one of the Commission’s key findings, a spike of commentary and media and professional attention focused firmly on culture.

Whilst focused on financial services organisations, regulators such as ASIC have indicated that the Hayne Royal Commission recommendations on culture will be the standard that will be applied to all organisations in exercising their supervisory duties. In addition, the ASX has released the 4th Edition of its Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations, of which Recommendation 3 relates directly to culture.

All of this means that culture is no longer an esoteric, warm and fuzzy concept, but a source of potential individual liability of Boards and individual directors if there are lapses of culture resulting in misconduct/and or loss. Not necessarily misconduct of directors themselves, but potentially the misconduct of a middle manager in the organisation whose actions can be traced back to a lapse in the overall culture of the organisation.

In our view culture has never been an esoteric, warm and fuzzy concept, but a key driver of marketplace success. There has always been a potential upside for organisations that measure and manage culture in achieving sustained success, and a potential downside (sometimes catastrophic) for organisations that do not manage their culture – usually by falling into the trap of the end justifying the means, driven by shareholder primacy.

Banking Royal Commission Recommendation 5.6

The start point for understanding the role of a Board in assessing and managing culture is recommendation 5.6 of the Hayne Royal Commission, which states that financial services entities:

“…should, as often as reasonably possible, take proper steps to:

· Assess the entity’s culture and governance;

· Identify any problems with that culture and governance;

· Deal with those problems; and

· Determine whether the changes it has made have been effective.” (1)

Commissioner Hayne went to great lengths to emphasise that Recommendation 5.6 involves more than just measuring an entity’s risk culture and is much more than a “box-ticking” (2) exercise. On measuring culture Commissioner Hayne observed:

“Its proper application demands intellectual drive, honesty and rigour. It demands thought, work and action informed by what has happened in the past, why it happened and what steps are now proposed to prevent its recurrence” (3)

Hayne stated clearly that the “primary responsibility for misconduct…lies with the entities concerned and those who manage and control them: their boards and senior management.” (4)

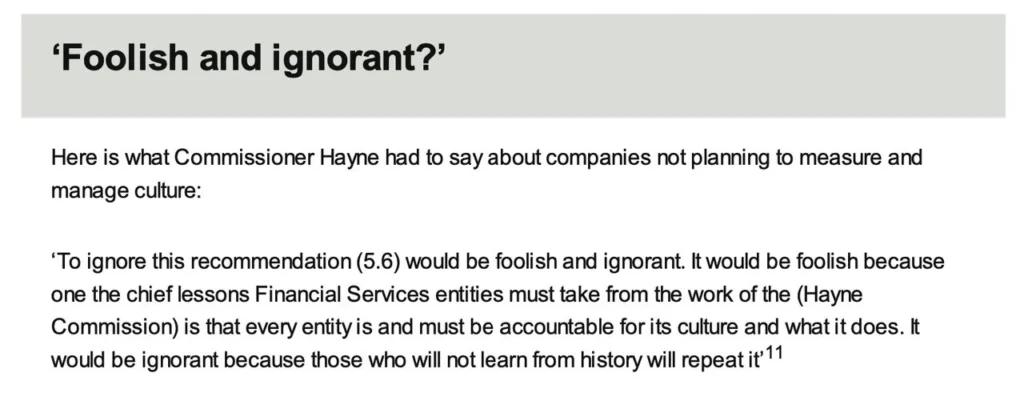

Furthermore he did not hold back in stating that to ignore Recommendation 5.6 would be “foolish and ignorant”. (5)

Whilst Recommendation 5.6 was specific to the Financial Services sector, ASIC has recently established a “Why Not Litigate” approach to enforcement. This enforcement philosophy should be viewed in the context of the ASIC Corporate Plan 2019 – 2023 which highlights corporate culture and governance as a key area of focus for ASIC, “prioritising enforcement cases that hold individuals to account for governance failure that result in harm”. (6)

Added to this is Recommendation 3 of the Fourth Edition of the ASX Governance Council, which requires a listed entity to “instil & continually reinforce a culture of acting lawfully, ethically & responsibly”. (7)

With ASX applying an “If Not, Why Not” (8) approach to the adoption of Recommendation 3, there could be potential market implications for listed entities that are not able to clearly demonstrate how they are instilling and continually reinforcing a culture of acting lawfully, ethically and responsibly.

It can be argued that the combination of Hayne Recommendation 5.6 and ASX 4th Edition Recommendation 3 provide a clear framework for ASIC and other regulatory bodies to assess whether an entity’s directors and officers have fulfilled the business judgement rule under s.180 of the Corporations Act 2001.

In other words, unless Company Directors and Officers can demonstrate that they have taken reasonable steps to assess culture and governance, they are potentially in breach of their obligation to discharge their power and duties with care and diligence under s.180.

So, this begs the question – what is Culture?

Even though organisational culture has been an area of rigorous academic research, it has been the subject of debate over the years. It has been a term that has been used loosely in various contexts professionally, in the mainstream media and colloquially.

Fortunately Commissioner Hayne provided us with a clear definition. He defined culture as:

“the shared values and norms that shape behaviours and mindsets within the entity” (9)

Or more simply Commissioner Hayne observed that culture is “what people do when no one is watching”. (10)

In our view Hayne Recommendation 5.6 and ASX 4th Edition Recommendation 3, provide a clear and compelling obligation on Boards and Company officers to measure culture – to assess the shared values and norms that shape the behaviour and mindsets within a Company.

Companies and Boards that are not planning to assess and mange culture are ‘foolish and ignorant’ (to quote Commissioner Hayne), and potentially expose individual directors and company officers to litigation for failing to exercise the required care and diligence required by s.180 of the Corporations Act 2001

Developing a Culture Strategy

Having established a clear imperative on Boards to measure and manage culture, the challenge for many organisations and directors is how to do this. The answer lies in taking a rigorous and disciplined approach to the assessment and management of culture.

Organisational culture has been well researched for many decades. Fortunately there is a high degree of alignment between the definition of culture used by Commissioner Hayne and the views of two of the leading academic thinkers and researchers in this field.

Ed Schein defines culture as

“..the accumulated learning of the group that is a pattern or system of beliefs, values and behavioural norms that come to be taken for granted as basic assumptions and eventually drop out of awareness” (12)

Or to put it another way in his own words,

“Culture is telling you moment to moment what to do.” (13)

He also suggests that knowing this then, the management of culture is probably the most important thing that leaders do and added that if they are not managing culture then it is undoubtedly managing them.

Rob Cooke defines organisational culture as

“the shared beliefs, norms and expectations that govern the way people approach their work and interact with each other.” (14)

Much of the recent discussion on organisational culture within Australia has focused on risk and managing the downside of poor behaviour. Yet it should be clear from the Hayne, Schein and Cooke definitions that there are considerable upside opportunities to be gained from focusing on behaviours which optimise results, are in pursuit of doing the right thing, treat people fairly and equitably and build trusting relationships, achieving sustainable results over the long term.

Organisational Context – A roadmap for change

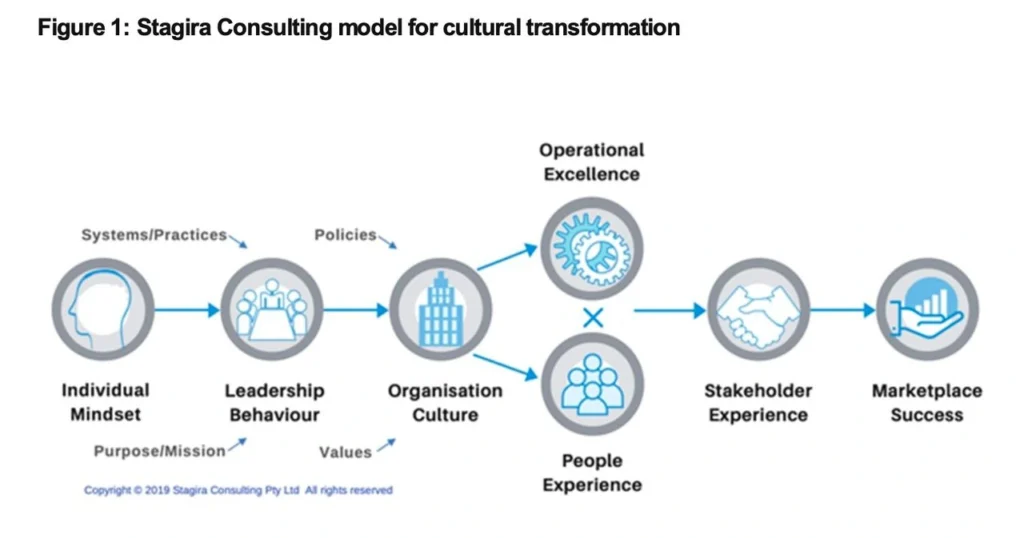

In order for a culture strategy to be more than a “box ticking” exercise, culture should be viewed in the context of an overall organisational construct – the key drivers of culture and how culture contributes to optimal organisational outcomes.

We have developed a model which shows these relationship (Figure 1)

We recommend that organisations start with the end in mind, and for commercial organisations this is usually sustainable Marketplace Success. Most organisations are usually clear about what success looks like for them. However we do encourage organisations to define Marketplace Success in more than just in financial or profit terms.

The key to Marketplace Success is to provide an experience to Stakeholders that builds strong sustainable relationships and partnerships founded on trust. Commercial success is fundamentally about developing quality relationships- between people and brands/products/services on the one hand, and customers/consumers on the other.

Strong relationships build good outcomes such as customers staying with you, recommending your products and services to others, and having a greater willingness to do more with you. The key to strong relationships is the behaviour that stakeholders experience, or attribute to an organisation, its people or brands/products/services, as you interact with these.

Clearly there are some behaviours that build strong trusting relationships and there are others diminish or destroy relationships. In a fast changing, increasingly transparent and networked world, it is vitally important to behave in a way that builds strong trusting relationships and provides a positive experience to all the stakeholders.

Central to this model is organisational culture – the ‘shared beliefs, norms and expectations’ that shape the actual behaviour which impacts upon a range of desired outcomes. Culture impacts directly upon operational excellence, how well everyone works together to meet the needs of external stakeholders.

Culture also has a direct impact upon the experience that people have as they work together within an organisation, and consequently on their levels of engagement or passion and commitment to do a great job for customers etc.

Research has shown that the behaviour of leaders has the greatest potential impact on organisational culture. Hence an investment in building the insight, desire and capacity of leaders to change, to develop a more constructive style and to encourage others to behave in a more constructive way, is essential in order to achieve sustainable cultural change.

Assessing Culture

The start point for developing a culture strategy is gaining an understanding of the current culture, from which insights can be gained, culture targets can be set and actions agreed to achieve desired outcomes.

Hayne Recommendation 5.6 states that entities should take proper steps to assess culture. In other words take proper steps to assess the ‘shared values and norms that shape behaviours and mindsets within the entity’.

So what does assess mean?

The Oxford Dictionary definition is ‘to estimate or evaluate the nature, ability or quality of something’.

Assessment can involve either:

· The judgement or opinion of a person or group based on what they think eg ‘I think we have a culture of innovation’

· Qualitative evaluation using agreed criteria and feedback from a selected group, or

· Quantitative evaluation ie measurement, using a statistically reliable and valid instrument.

Our view is that 5.6 Hayne Recommendation involves much more than mere judgement or opinion. Indeed Commissioner Hayne stated that the proper application of 5.6 requires ‘intellectual drive, honesty and rigour.’

Assuming statistical reliability and validity, a quantifiable evaluation or measurement will nearly always produce a higher quality evaluation than a qualitative assessment. It will also allow for more accurate remeasurement as recommended in 5.6.

However, qualitative assessments can be very useful in digging deeper into areas that a quantitative assessment may not measure.

Let’s use a simple example to illustrate this point.

Imagine you are purchasing a car that you really want to buy. However you are not sure whether it is going to fit into the garage. You could:

1. Use your own judgement (which could be biased by the fact that you really want this car)

2. Seek other people’s views ie make a qualitative evaluation. The quality of the assessment will be driven by whether people have seen the car and your garage, their ability to estimate 3D dimensions, combined with the number of informed views sought

3. Take out a tape measure and measure both the car and the garage. ie make a quantitative evaluation

You can see in this simple example that a quantitative evaluation will produce a higher quality answer to the specific question.

A qualitative approach may have produced the same outcome, but without the same degree of reliability. However in the process of seeking informed views, other information that may not have been initially sought may have been unveiled, eg that the same car could be found cheaper online.

Therefore in assessing culture, quantitative and qualitative both have an important role to play:

· Quantitative to produce a statistically valid, reliable and externally normed measure that allows future measurement, tracking of progress and more accurate reporting.

· Qualitative assessment to uncover underlying mindsets, to gain a better and deeper understanding of the results, and to seek feedback on items not measured quantifiably.

Can culture be quantifiably measured?

Measuring the size of a car is straightforward. But what about quantifiably measuring the ‘shared values and norms that shape behaviours and mindsets within an entity’. Is this even possible?

The measurement of culture is widely regarded as very difficult, if not impossible, by many organisations. The reality is that several decades of rigorous scientific research on organisational culture has produced reliable and robust measurement instruments.

However the vast majority of companies in Australia are not measuring culture – which puts them potentially at odds with Hayne Recommendation 5.6 and ASX 4th Edition Principle 3. Before we discuss how to measure culture, let examine our view as to why many Australian organisations are not measuring culture. We see two key reasons:

(a) An over-reliance on the views of CEO’s on culture

As mentioned earlier, the least robust assessment of culture is the mere judgement or opinion of one or a handful or people. In the absence of a rigorous measurement and independent inquiry, the Board’s understanding of organisational culture maybe influenced by the opinion of the CEO.

This is not to suggest that a CEO would not represent their perspective in good faith.

However the potential pitfall of Boards relying on untested judgements and opinions of the CEO was demonstrated in a recent survey and white paper published by AHRI and Insync in September 2019. Amongst their findings on workplace culture was the insight that “CEO’s have trouble seeing culture problems” (15)

Survey data presented in their paper showed a significant gap between CEO’s views on cultural markers in their organisation and the views of others (including Executives/Senior Managers). (16)

This should ring alarm bells for all Boards who may have previously relied on the views of CEO’s, and perhaps other members of the senior leadership team, on the culture of their organisation. The new requirements on Boards necessitate a higher level of due diligence including the use of independent and statistically valid and reliable tools.

(b) Many companies are under the misapprehension that they are already measuring culture

Many companies think they are measuring culture, when in fact they are measuring something different.

A review of the annual reports and sustainability reports of ASX100 companies show many organisations using measures such as talent and/or engagement, but do not articulate any measures of culture.

Both talent and engagement are very important people measures for marketplace success. However they are not measures of culture.

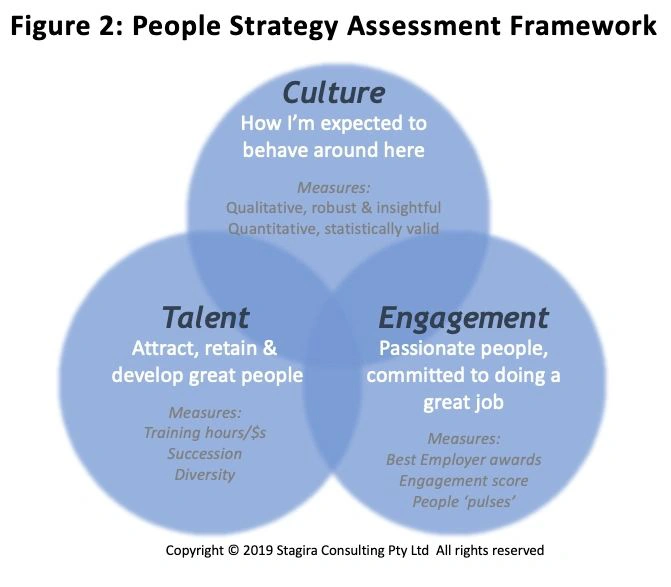

Let’s briefly distinguish between Talent, Engagement and Culture, which is shown in Figure 2.

Talent – there is no doubt that attraction, retention, development and deployment of talent against the strategic aspirations of an organisation is critical. The quality of an organisation’s talent sets the high water mark for marketplace success. Organisations almost universally understand the importance of talent, and use measures such as bench strength, diversity and training hours per employee to track progress.

Engagement – simply having talented people is not sufficient to achieve sustained marketplace success, unless talented people are also passionate about the organisation and its products/services, believe in its purpose, and strive for results. Engagement surveys are a highly effective method of measuring these attributes, and are popular amongst most organisations.

Culture – as discussed – the shared values and norms that shape behaviours and mindsets within a company.

It is more than possible, and unfortunately common, for a talented, highly engaged workforce/team to underperform, or worse still, produce catastrophic results if the underlying culture is suboptimal.